Link to paper

The full paper is available here.

You can also find the paper on PapersWithCode here.

Abstract

- Research on adversarial machine learning has increased in recent years.

- Attackers use simple tactics to subvert ML-driven systems.

- This paper aims to bridge the gap between researchers and practitioners.

Paper Content

I. introduction

- Protecting ML models is not a leading security concern for practitioners

- Attackers can break ML systems by guessing or using coarse heuristics

- Defensive recommendations are more broad than adversarial training

- ML models are often not directly observable by attackers

- Researchers should not rely on “security by obscurity”

- Thousands of papers have showcased successful security violations of ML models

- Gap between adversarial ML research and practice is real

- Four positions to close the gap between research and practice

Arxiv:2212.14315v1 [cs.cr] 29 dec 2022

- We present three case studies to show practical insights.

- We analyze recent adversarial ML papers to highlight trends and blind spots.

Ii. revisiting machine learning security

- Review of foundations of three pillars of paper: machine learning systems, security of machine learning, practical cybersecurity

- Comparison of paper with related work

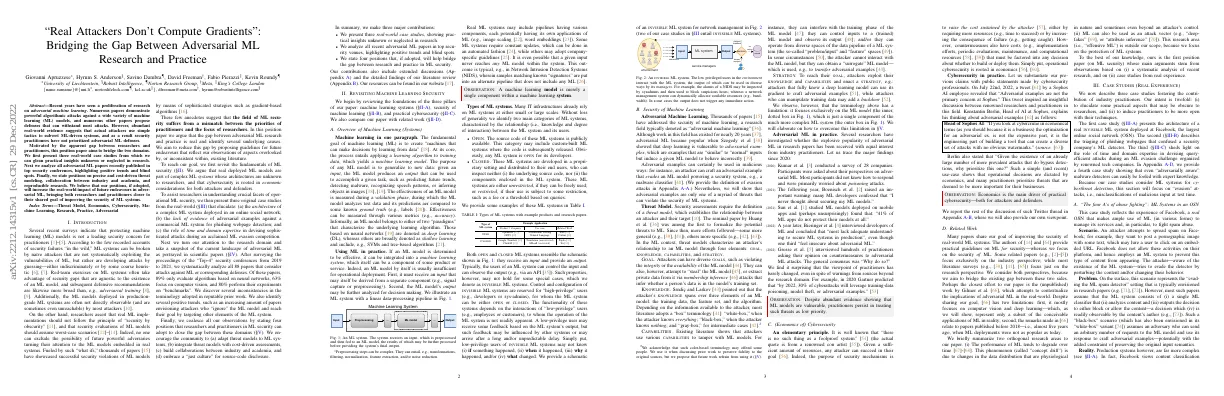

A. overview of machine learning (systems)

- Machine learning (ML) is a process of creating machines that can make decisions by learning from data

- ML models are used to predict future trends, detect malware, recognize speech patterns, or infer objects in images

- ML models are measured for effectiveness during a validation phase

- ML models can be divided into two paradigms: deep learning (DL) and shallow learning

- ML models must be integrated into a machine learning system for operational deployment

Input

- Preprocessing of ML model is necessary

- Preprocessing can improve accuracy of ML model

… output

Machine learning system

- Preprocessing steps can be complex

- ML systems may include pipelines with various components

- ML systems require constant updates

- ML systems can be OPEN or CLOSED

B. security of machine learning

- Adversarial Machine Learning is a research field that has existed for nearly 20 years

- Adversarial examples can be used to make ML models behave incorrectly

- Security assessments require the definition of a threat model

- Attackers can have diverse goals, such as violating the integrity or availability of the ML model

- Attackers can have different levels of knowledge about the ML model

- Attackers can use various capabilities to tamper with ML models

- Attackers use their knowledge and capabilities to enact a strategy to reach their goal

- Despite evidence of ML models being vulnerable, practitioners treat such threats as low priority

C. (economics of) cybersecurity

- Security mechanisms are designed to make it more difficult and costly for attackers to succeed.

- Countermeasures also have costs associated with them.

- Cybersecurity decisions are based on economics.

D. related work

- Goal of paper is to improve security of real-world ML systems

- Paper considers both industry and research perspectives

- Paper is the first to use systematic analysis and case studies from real experience

- Two orthogonal research areas discussed: concept drift and offensive ML

Iii. case studies (real experience)

- Describes 3 case studies to elucidate practical aspects and induce practitioners to be more open

- Focuses on “evasion” attacks, i.e., misclassifications of malicious input at test time

A. “the four a’s of abuse fighting”: ml systems in an osn

- Facebook uses ML to prevent spam abuse

- Attacker tries to evade ML system by changing content and behavior

- Most research papers assume ML system consists of single ML classifier

- Facebook views content classification as last line of defense

- System consists of four interconnected defensive layers: Automation, Access, Activity, and Application

- Attacker must bypass all layers to be successful

- Automation layer prevents black-box attack strategies

- Access layer analyzes write requests to determine if permission was obtained legitimately

- Activity layer looks for differences between malicious and normal user behavior

- Application layer uses deep learning models to detect prohibited content

- Attacker must try many different evasion strategies

- Response layer decides which action to take

- Real ML systems can be thwarted via simple tactics

B. are there adversarial examples in the wild (web)?

- AI Incident Database contains over 1,600 reports of AI failures

- Querying the database with keywords “evasion” and “adversarial machine learning” yielded only 2 and 6 results respectively

- Asked a leading cybersecurity company if they encounter adversarial examples when manually triaging security incidents

- Problem of phishing webpage detection

- ML system is a commercial-grade detector composed of diverse modules

- ML system uses active learning to output a “phishing confidence” score

- Searched for adversarial examples in ML system’s usage logs

- Analyzed hundreds of thousands of inputs, 9,174 flagged as “uncertain”

- Visually inspected each sample and stopped once 100 positive answers

- Found cropping, masking, stretching, and/or blurring techniques used to fool ML systems

- Found samples with different logo, “company name style” attacks, and removing logo/company name

- Rarely encountered “multiple form/image” and “background pattern” attacks

- Attackers rely on simple yet effective strategies

- Releasing 100 evasive webpages analyzed in case study

C. in-depth analysis of an ml evasion competition

- An “anti-phishing evasion” competition was organized by industry practitioners in ML security

- Contestants were given 10 phishing webpages and challenged to manipulate them to evade 7 ML phishing detectors

- Winners were determined by successful evasions and number of queries issued to the detectors

- 4 teams achieved a perfect score of 70 points

- 1st-place team used sophisticated HTML manipulations and domain expertise

- 4th-place team used automation and likely required little human effort

- Measuring attack efficiency with query counts alone does not reveal the amount of time and domain expertise required

Iv. snapshot of adversarial ml research

- Analyze research domain

- Identify research trends and blind spots

- Overview of analysis

- Focus on positive trends of threat models

- Highlight inconsistent terminology

A. overview

- 72% focus on attacks

- 28% focus on defenses

- 52% envision “evasion” attacks

- 89% consider only deep learning algorithms

B. positive findings in threat models of attack papers

- Constrained adversaries are increasingly being considered in attack papers.

- Nasr et al. and Barradas et al. consider attacks against ML-NIDS and website fingerprinting respectively.

- Chen et al. and Zheng et al. propose strategies for attacking ML systems for automated speech recognition.

- Xiao et al. and Nassi et al. target production-grade ML systems.

- Attackers may succeed without fooling the ML model or the entire ML system.

C. positive findings in threat models of defense papers

- 24 out of 88 papers consider defenses

- Defense papers focus on cost of countermeasures

- Common approach is to consider adversaries with perfect knowledge

- Creating an OPEN ML system is dangerous

- Defenses against limited-knowledge attackers exist

- Limited-knowledge attackers can be as dangerous as omniscient ones

D. inconsistencies that may harm future research

- Focused on threat models and attacker knowledge and capabilities

- Common terms “white-box” and “black-box” used to denote different degrees of attacker knowledge

- Inconsistencies in definitions of “white-box”, “black-box” and “gray-box”

- Attacker knowledge and capabilities difficult to identify

- Adapting threat models to ML systems

- Integrating threat models with cost-driven assessments

- Encouraging industry and academia to collaborate

- Embracing a “just culture” for reproducible research

A. adapting threat models to ml systems

- Threat models must cover the entire ML system

- Real attackers have broader goals than attacking a single ML model

- Knowledge assumptions should cover all components of ML systems

- Capabilities must consider all components of the ML system

- Attackers can adopt strategies that “ignore” the specific ML models

- Box-based terminology should be avoided

- Access should be precise and specified for every component of the ML system

- Evasion should be used to denote the attacker’s goal

- Adversarial should only be used for established notions

B. cost-driven security assessments

- Recent papers have not given enough consideration to the economics of cybersecurity.

- Threat models should include cost-driven assessments for both the attacker and the defender.

- System designers should prioritize threats that are more likely to occur in the wild.

- Real attackers operate with a cost/benefit mindset.

Context. biggio and roli

- Weigh potential benefit to attacker and cost to reap benefit

- Simulate attack and gauge corresponding damage

- Estimate costs of countermeasures

- Human cost factor should be accounted for

C. collaborations between industry and academia

- 20% of analyzed papers consider real ML systems

- 90% of papers only consider deep learning algorithms

- Practitioners and academics must collaborate to improve security of ML systems

- Most real ML systems are invisible or closed, preventing researchers from understanding how they work

- Companies can offer bug-bounty programs or dedicate resources to processing researcher requests

D. just culture and reproducible research

- Half of the papers analyzed do not release their source code.

- A “just culture” should be promoted to encourage source-code disclosure.

- A “just culture” is an approach that assumes mistakes occur and uses them as learning experiences.

- Source-code disclosure can help spot flaws and turn negative results into positive outcomes.

Vi. conclusions

- More reproducible research is needed

- Threat models for entire ML systems should be described using precise terminology

- Cost-driven assessments should factor in human effort

- Active collaboration with practitioners from industry should be fostered

- Novel techniques for the forensics of ML incidents should be developed

B. researchers vs practitioners (twitter thread in §ii-c)

- Discussion between Battista Biggio, Joshua Saxe, and Konstantin Berlin

- Viewpoint on Twitter thread mentioned in section II-C

J1) why robustness to adversarial examples isn’t a first-priority

- Researchers and practitioners are solving different problems

- Companies prioritize threats that operate at scale

- Attackers envisioned in many adversarial ML papers tend to be subtle

- Better cooperation between industry and academia would kick-start novel research efforts

C. further considerations on our third case study ( §iii-c)

- Queries and submissions: queries are individual API calls, submissions are adversarial webpages

- Interpretation: all teams had the same objective, 3rd made the first submission, 3rd completed the attack with 608 queries, 4th made 9982 queries, 1st and 2nd made their first submission on day 31, 2nd completed the attack with 343 queries, 1st completed the attack with 320 queries

- Without 3rd’s effort, 1st and 2nd would not have achieved perfect evasion

- Model replication attacks require more queries but less human effort

D. case study: malware competition (2020)

- Defense challenge: Participants had to submit ML systems for malware detection that met certain performance metrics.

- Attack challenge: Participants were given 50 PE malware samples and allowed to manipulate them to evade ML-based detectors.

- Defense challenge winner: Quiring et al. integrated typical approaches to counter malware and a defensive layer to anticipate adaptive attackers.

- Attack challenge winner: Ceschin et al. induced all of their samples to evade all the considered detectors by embedding the malware payload into another binary.

- Observation: Bypassing some ML systems may not require sophisticated techniques.

E. example: gains and losses is not a zero-sum game

- Attacker gains from successful evasion of ML-based malware detector

- Customer may pay ransom or not

- Developer of detector may lose or gain depending on contract terms

F. unreproducible papers

- Difficult to meet ideal of releasing source code and public datasets

- User privacy must be respected

- Employers may impose constraints on releasing source code

- Descriptive details and technical artifacts should be provided to maximize reproducibility

- Papers should describe ML systems and models in detail, evaluate on public datasets, and describe nuances of private datasets

G. discussion (with the reviewers)

- Spammers and regular users have different behavior patterns

- Defenses should be robust in a query-only setting

- Domain knowledge is hard to quantify

- Everything is adversarial from a security standpoint

- Nation-state adversaries have unlimited resources

- 88 papers were analyzed for position paper

- Most 2019 papers were in ML security sessions

- 2021 papers had sessions dedicated to specific attacks

- Some papers had similar contributions

- Analysis was done in pairs to reduce bias

- Questions were asked to derive knowledge

- Trivia was provided about papers

B. research questions

- Examined 88 papers

- Asked 12 research questions, divided into two groups

- Generic Questions (G1-G8) provide broad overview of research trends

- Threat-Model Questions (T1-T4) relate to threat model envisioned in paper

- Answers to questions provided in Figs. 7-13 and Table IV