Link to paper

The full paper is available here.

You can also find the paper on PapersWithCode here.

Abstract

- Neurons can emit action potentials in different patterns.

- Electrophysiologists labeled action potentials emitted at a high frequency as “bursts”.

- The burst coding hypothesis suggests that the neural code has three syllables: silences, spikes and bursts.

- Evidence is reviewed to support the ternary code in terms of mechanisms for burst generation, synaptic transmission and synaptic plasticity.

- Learning and attention theories are reviewed that benefit from the triad.

Paper Content

Introduction

- Problem of neural coding is to interpret neuronal signals

- Neurons represent input features with number of action potentials

- High impulse frequencies imply presence of feature

- Inputs are represented by computing averages

- Not all spikes are equal, code is ternary

- Evidence for burst coding hypothesis in 3 variations

- Alignment between generation and synaptic mechanisms

- Nervous system can process two streams of information simultaneously

What is a burst?

- Brain may use a ternary code

- Neurons may display bimodal or unimodal interspike interval distributions

- A unimodal distribution of intervals is not necessarily associated with a drop of information transmitted using a burst code

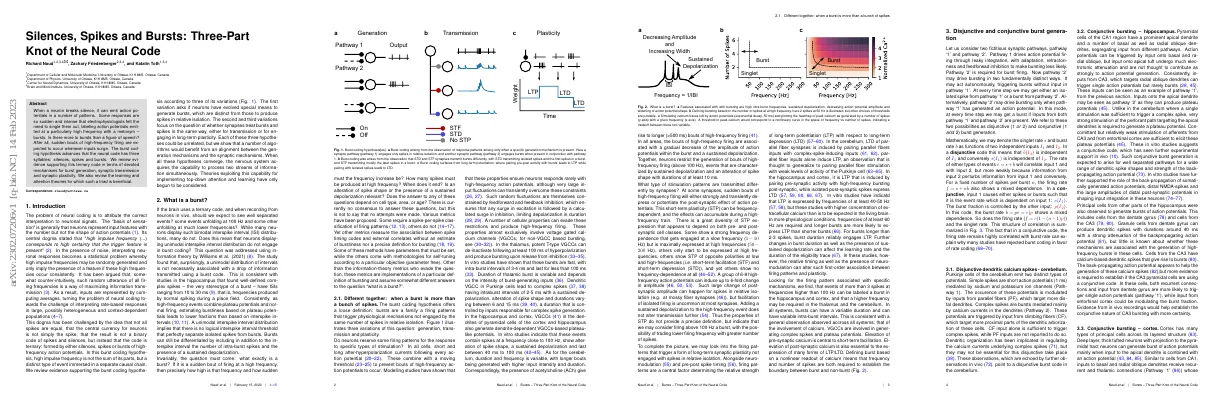

- Burst coding hypothesis suggests that bursts are a family of firing patterns that trigger physiological mechanisms not engaged by the same number of spikes in relative isolation

- Features associated with bursting are high intra-burst frequencies, sustained depolarization, decreasing action potential amplitude and widening of action potential shape

- Defining bursting based on the number of spikes at a high frequency

- Synapses can show frequency-dependent short-term plasticity

- Firing patterns can trigger long-term synaptic plasticity

- Events of more than 3 spikes at frequencies higher than 100 Hz can be labeled a burst in the hippocampus and cortex

- A higher frequency may be required in the thalamus and the cerebellum

- Bursts can have a variable duration and can have variable intra-burst intervals

- Defining burst based on a nonlinear readout of calcium means that frequency and number of spikes are both required to establish the boundary between burst and non-burst

Disjunctive and conjunctive burst generation

- Pathway 1 and Pathway 2 are two fictitious synaptic pathways

- Pathway 1 drives action potential firing and Pathway 2 is required for burst firing

- Pathway 2 can act autonomously or drive bursting only when Pathway 1 has generated an action potential

- These two possibilities are referred to as disjunctive and conjunctive burst generation

- The rate of either types of events (spikes or bursts) is dependent on input 1 and input 2

- The firing rate is highly correlated with burst rate, which explains why many studies have rejected burst coding in favor of rate coding

Disjunctive dendritic calcium spikes -cerebellum.

- Purkinje cells emit two types of potentials: simple spikes and complex spikes

- Simple spikes are short action potentials mediated by sodium and potassium ion channels

- Complex spikes are bursts mediated mainly by calcium currents in the dendrites

- Complex spikes are triggered by input from climbing fibers, not parallel fibers

- Dendritic organization may regulate calcium currents underlying complex spikes

Conjunctive bursting -hippocampus.

- Pyramidal cells of the CA1 region have a prominent apical dendrite and a number of basal and radial oblique dendrites

- Input onto basal and radial oblique can trigger action potentials, but input onto apical tuft undergoes electrotonic attenuation

- Inputs from CA3 can trigger single action potentials but rarely bursts

- In vitro studies suggest a conjunctive code, which has seen further experimental support in vivo

- Backpropagating action potentials, distal NMDA-spikes and large amplitudes of distal post-synaptic potentials shape input integration in these neurons

- Granule cells from dentate gyrus and cells from CA3 can produce bursts of action potentials

Conjunctive bursting -cortex.

- Cortex has many types of principal cells

- Deep layer neurons can generate bursts of action potentials

- Inputs to basal and radial oblique dendrites receive recurrent and thalamic connections

- Bursting arises when one or both input pathways are active

- Correlation between singlet rate, burst rate, event rate, burst fraction, and firing rate with either inputs

- Cortex uses a conjunctive code where feedforward and feedback inputs are required to generate bursts

- Potent feedforward inhibition counteracts ability to generate action potentials

- T-type voltage-gated calcium channels control burstiness in thalamic relay neurons

- Controlling hyperpolarization controls burst fraction without affecting firing rate

Burst-dependent synaptic plasticity

- LTP is a cellular basis for learning and memory

- LTP requires NMDARs, elevated post-synaptic calcium and local glutamate release

- Calcium elevation at the synapse can come from NMDAR-mediated currents, local release from calcium stores or VGCC

- Post-synaptic bursting can control LTP expression

- Hebb’s theory needs to be revised when bursting is not triggered by the same pathway undergoing the potentiation

- In vitro recordings have confirmed a central role of post-synaptic bursting in the expression of LTP

- Plasticity in the cerebellum also shows burst dependence

- Burst-dependent learning rules in the electric sense of electric fish

Differential transmission of firing patterns

- Transmission must be frequency dependent to separate bursts from single spikes post-synaptically.

- Francis Crick hypothesized properties of synapses called von der Marlsburg synapses.

- STP is well established and can be triggered by burst-like events with a frequency closer to 100 Hz.

- STP can demix a mixture of spikes and bursts and can communicate independent information to different post-synaptic targets.

Cortex.

- Study surveyed over 20,000 synaptic pairs in animal slices and over 2500 in human tissue

- Most connections showed some level of STD over a wide range of stimulation frequencies

- Connections to and from PV-positive cells tend to show depression

- Some synapses show STD with a cutoff at 50 or 100 Hz

- Connections onto and from SST- and VIP-positive cells display STF

- Combining synaptic properties in cellular connectivity motifs can select bursts

- Polarization of local connections in terms of STD and STF is reflected in a polarization of impinging pathways

Hippocampus.

- CA1 pyramidal cells receive inputs from two main pathways: the perforant path and the schaffer collateral

- Perforant path inputs target mainly apical dendrites and NPY-positive cells

- Schaffer collateral inputs target mainly apical oblique dendrites, PV-, SST-as well as NPY-positive cells

- All inputs show short-term facilitation with frequency dependence

- CA1 pyramidal neurons project to multiple targets, with many connections going to the subiculum, which also display short-term facilitation

Cerebellum.

- Purkinje cells are the most numerous cells in the cerebellum.

- They receive inputs from granule cells and the inferior olive.

- PF inputs show STF, while CF inputs show an absence of short-term plasticity.

Thalamus.

- Sensory thalamus receives feedforward information from the senses.

- Thalamocortical afferents from sensory thalamus to sensory cortices show STD.

- Cortex sends feedback information to sensory thalamus with STF projections.

- Cortex sends feedforward information to higher-order thalamus with STD.

What logic.

- Inputs to principal cells are both STD and STF in the thalamus, more STD in the cortex and strictly STF in the hippocampus.

- Outputs from principal cells are strictly STD in the cerebellum and thalamus, but STF in the hippocampus.

- STD is used to communicate feedforward information, supported by the thalamus and cortex.

- STF inputs are used to control LTP in the cortex, hippocampus and cerebellum.

Algorithmic requirements for burst coding

- Representing information using two distinct types of activity can be beneficial for the nervous system

- Algorithms that require two streams of information can be implemented using a ternary code

- Supervised learning algorithms require two types of information

- Reinforcement learning algorithms benefit from burst coding

- Unsupervised learning algorithms require two types of information

- Attention signals take the form of gain modulation and plasticity gating, which can be facilitated by burst coding

Bursting in vivo

- Bursts occur spontaneously in awake and anesthetized animals

- Bursting is correlated with firing rate

- Different methods of measuring burst fractions lead to different results

- Anesthesia and sleep are associated with higher burstiness

- Relationship between arousal and bursting may extend to other areas

- Burst fraction in awake states is typically between 15-40%

- Variations in burstiness across areas indicate higher propensity in visual and prefrontal areas

Attention states.

- Visual attention enhances or suppresses saliency of locations and features in the visual field.

- Modulations of local field potential and noise correlations are observed in the visual cortex.

- Individual neurons show increases in firing rate and decreases in trial-to-trial variability.

- Direct measures of bursting modulation with attention have been observed in the visual cortex.

- When attention is directed onto a neuron’s receptive field, there is an increase in firing rate and a reduction in burstiness.

- In contrast, attention-dependent increases in bursting have been observed in anterior cingulate and prefrontal cortex.

- In the primary somatosensory cortex of rodents, changes in bursting correlate with a shift in perceptual performance.

Learning.

- Place fields are more likely to form in cells that produce bursts

- Correlation between spontaneous plateau potentials and place field formation

- Artificial induction of plateau potentials can give rise to a new place field

- Inputs from entorhinal cortex, CA3 and disinhibition from SST-positive are required for in vivo bursting

- EC bursting acts as an instructive signal

- High-frequency bursting of long duration occurs in cortex during associative learning tasks

- Blocking feedforward or feedback connections blocks learning

- Dendrite targeting inhibition also blocks learning

- Burstiness encodes errors with a delay of 1 second

- Silencing pyramidal cell activity during reward period alters learning of sensory association task

Discussion

- Brain uses a ternary code for representing, transmitting and processing information

- Presence of burst-generating calcium spikes depend on neuron size, cortical layer and species

- Neurons engage in bursting in vivo and have burst-dependent transmission and synaptic plasticity

- GABAergic interneurons of the cortex may show burst-dependent transmission

- Putative GABAergic cells modulate bursting in an attention task in vivo

Conclusion

- Ternary neural code is a way for cells to communicate both elevated membrane potential and elevated levels of intracellular calcium

- Synaptic plasticity is engaged by elevated calcium rather than elevated membrane potential

- Burst coding hypothesis suggests that synaptic pathways engage either spikes or bursts

- Burst coding also arises from the observation that STD and STF synapses transmit bursts differently

- Burst coding surfaces from long-term potentiation, pairing pre-post activity with bursts leads to LTP

- Features associated with bursting are high intra-burst frequencies, sustained depolarization, decreasing action potential amplitude and widening of action potential shape